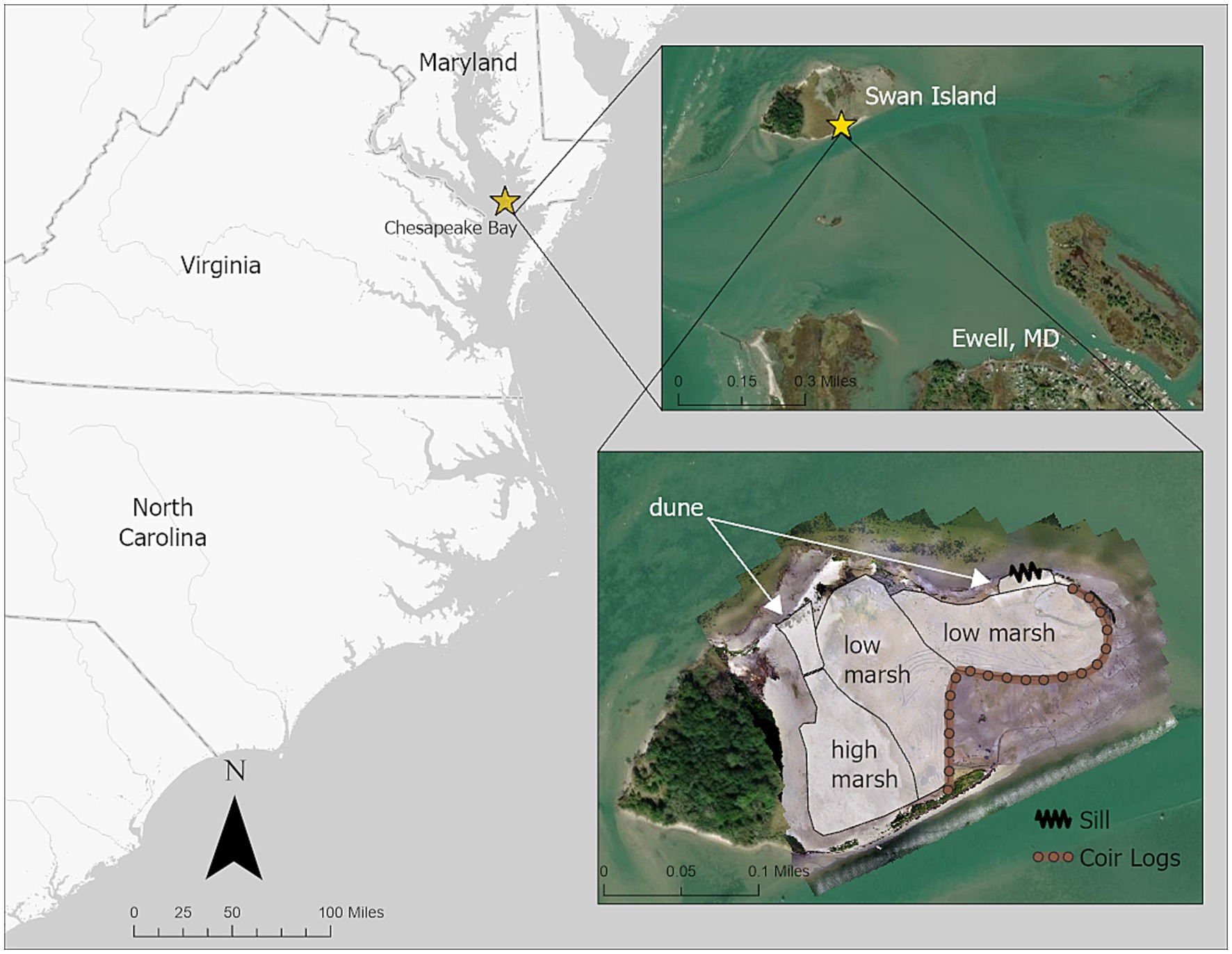

One of the more significant impediments to the widespread adoption of Nature-based Solutions (NBS) for coastal protection is a lack of empirical evidence about how NBS perform. NBS involves the intentional use of natural features like beaches, dunes, islands, marshes and mangroves, coral and oyster reefs, either alone or in combination with traditional gray infrastructure, like cement walls buried inside of sand dunes, to reduce risks to coastal hazards and deliver multiple environmental and socio-economic benefits. A recent paper addresses that knowledge gap by providing evidence from a project at Swan Island, Maryland, an uninhabited marsh island in mid-Chesapeake Bay, whose position renders it a natural wave break for the downwind town of Ewell, Maryland. The data presented documents early successes and highlights areas for improvement in similar future projects.

Despite rapidly expanding interest in the use of natural coastal habitats for their ability to protect against erosion and flooding, implementation of coastal natural infrastructure (NI) projects, a type of NBS, has been limited to date. Uncertainty over how the benefits of NI will change over time as they mature and adapt to changing environmental drivers, and a lack of well-documented demonstrations of NI, are often cited as roadblocks to their widespread acceptance. New research fills that knowledge gap by describing implementation and early (3 years post-implementation) monitoring results of the NI project at Swan Island. Prior to project implementation, Swan Island had experienced significant losses in area due to subsidence and erosion. To reverse this trend, the island was amended with dredged sediments in the winter of 2018–2019. The overarching goal was to preserve the Island’s ability to serve as a wave break and make it more resilient to future sea level rise by increasing the elevation of the vegetated platform, while also increasing the diversity of habitats present.

A monitoring program was implemented immediately after sediment placement to document changes in the island footprint and topography over time and to evaluate the extent to which project goals were met. Data from the initial three years of this effort (2019 through 2022) indicate an island that is still actively evolving, and point to the need for rapid establishment of vegetative communities to ensure success of coastal NI.