Coastal Conversations Podcast: Episode 5

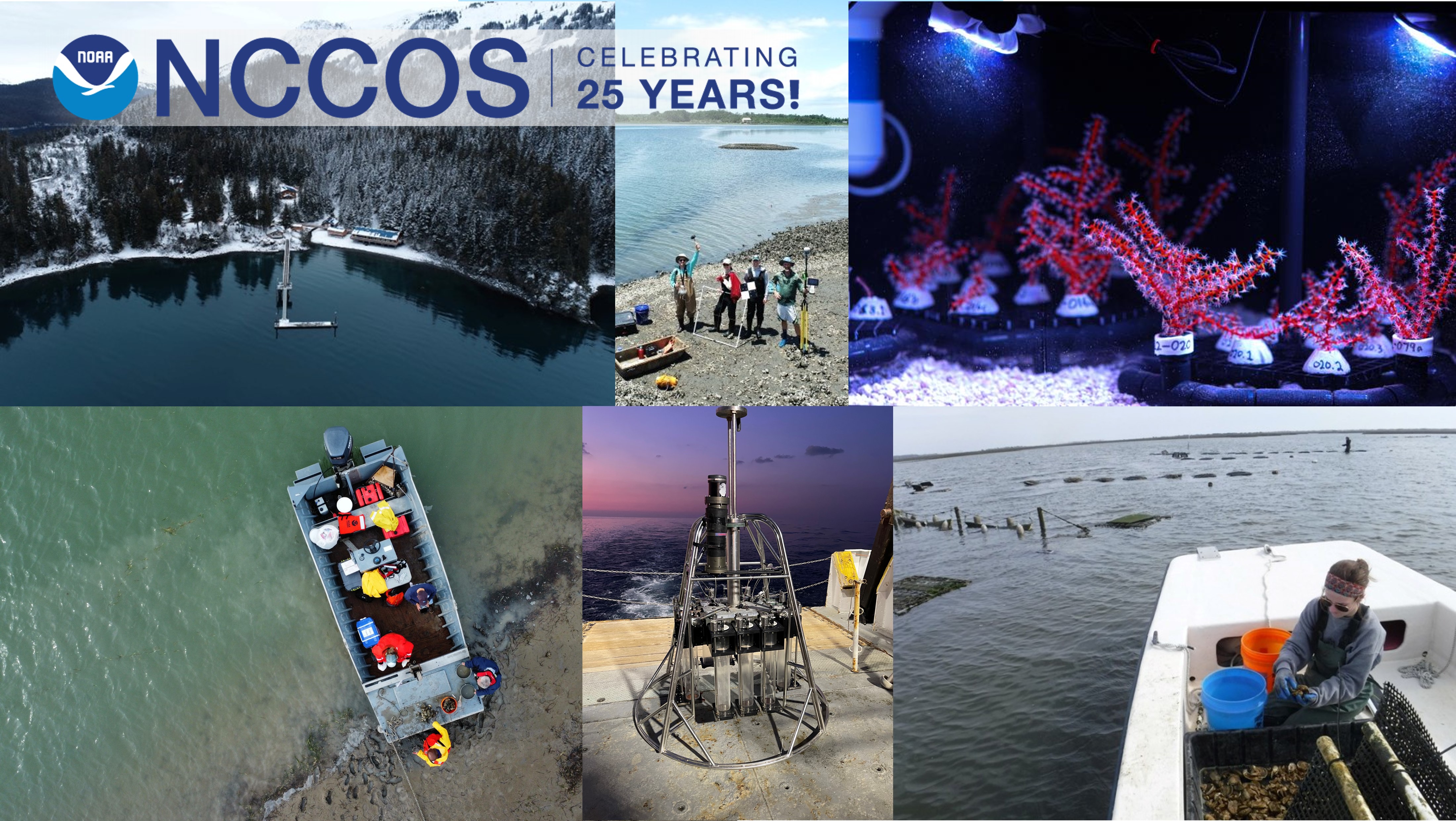

For 25 years NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science has been the focal point for NOAA’s coastal ocean science efforts. Follow our journey from 1999 and hear from some of our principal investigators that lead today’s research projects.

Listen here:

Episode Transcript

Kevin McMahon: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, more commonly known as NOAA, formed the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science in 1999 as the focal point for NOAA’s coastal ocean science efforts. The very first Director of NCCOS, Dr. Don Scavia, had this to say about the office’s establishment. “We wanted this program to be one place where both academic and agency scientists could get support for their regional research efforts. Naturally, we subjected the work to standard peer review. At the time there was no office that supported such work, especially the kind that has management implications” Twenty five years later, the Centers and labs that make up NCCOS continue this important work.

Welcome, you’re listening to Coastal Conversations, the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science podcast. I’m Kevin McMahon. Today we will be discussing 25 years of the NCCOS program: science serving coastal communities.

Advancing ecosystem science for conservation and sustainable use is just one of the drivers of our science. Here’s the Center’s current director, Dr. Sean Corson, explaining how the researchers are addressing these challenges.

Sean Corson: NCCOS researchers provide applied science for coastal communities. We’re conducting marine spatial planning analyses to help the country transition to renewable energy, protect at least 30 percent of our coastal ecosystems, and strengthen the U.S. economy by expanding commercial aquaculture. Our scientists are keeping beaches, drinking water, and seafood safe for the public by producing ecological forecasts, control, and mitigation strategies to address harmful algal blooms and pathogens. NCCOS is a leader in testing and identifying innovative solutions to address the social, ecological, and economic impacts of climate change to coastal communities nationwide.

Kevin: The Centers are spread across five locations. The Cooperative Oxford Lab in Oxford, MD; the Hollings Marine Lab in Charleston, SC; the Kasitsna Bay Lab near Homer, AK; the Beaufort Lab in Beaufort, NC; while NCCOS headquarters is located in Silver Spring, MD.

Coincidentally, the Beaufort Laboratory will be celebrating its own 125th anniversary later this year. Here’s Dr. Chris Taylor, a scientist at the lab, explaining the unique role the lab plays in the NCCOS mission.

Chris Taylor: As we recognize the milestone of 25 years at NCCOS, we’re also recognizing a significant milestone of one of our hubs of research here at the Beaufort Lab. The Beaufort Lab celebrates 125 years of federal marine science, research, and conservation this year. In 1899 government, and academic scientists already recognized the close connection between the coastal ocean and our reliance on natural resources that the ocean provides. They also recognized the dynamics of the ocean and its influence on natural resources, particularly at a place like Beaufort. Beaufort, NC is at the junction of a major inlet connecting the coastal ocean to one of the largest and most expansive estuarine systems on the Atlantic Coast. And Beaufort is also close proximity to one of the largest drivers of ocean productivity. A mere hours away is the Gulf Stream current. And the recognition of the changing of the dynamics and its impacts on the coastal communities and the marine systems is still something we’re witnessing today. And so the research on coastal resilience now at the forefront of the NCCOS portfolio has direct implications for, not only the communities that surround the lab here in Beaufort, but with impacts and applications across the entire nation.

The Beaufort Lab is home to one of the longest standing and accomplished dive programs in NOAA. Divers have made observations of rich and enormously spectacular detail of our underwater realm going back to the 1960s and 1970s. And still today we use SCUBA to make direct observations to monitor and assess the changes in our ocean habitats, from the hardbottom reefs, artificial reefs, and shipwrecks that are numerous off the coast of North Carolina, around the country to the coral reefs of Florida and the Caribbean and the Pacific Islands. But our approach to conducting these assessments and mapping these efforts is rapidly evolving. We’re now using underwater robots to carry the same sensors that divers use to carry, but they are significantly able to expand the extend of the observations and create maps that have richer detail and broader extent at a much finer resolution.

I’m excited for the future research here at Beaufort, where we can prepare the science that impacts the lives of coastal communities here and across the nation.

Providing evidence-based science products and tools that support informed decision-making is at the heart of the NCCOS’s mission. Our stakeholders look to us to provide relevant, timely, and actionable products and tools they need to make informed decisions. For example, our marine spatial planning products inform offshore aquaculture and wind energy placement, sanctuary site designations, and community vulnerability. By providing science products and tools, NCCOS helps communities plan for, adapt to, and reduce risks from the multiple challenges facing coastal communities.

This is Arliss Winship from our Mapping team, explaining the process of informing offshore wind energy placement.

Arliss Winship: For over a decade now, NCCOS, in partnership with the US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, has been mapping the spatial distributions of marine birds in U.S. waters to inform offshore wind energy development. Seabirds, sea ducks, and other marine birds range widely over the ocean while they are searching for food and during their seasonal migrations. As a result, many of these birds are likely to encounter wind energy developments at sea raising the potential for direct impacts like collision with wind turbines or indirect impacts like displacement from feeding areas, if birds tend to avoid wind developments. A key question that needs to be answered to assess those potential impacts is: Where and when do different species of birds occur in the marine environment? That’s where our maps come in.

We compile decades of bird counts at sea taken from ships and aircraft and then feed those data into statistical computer models to derive comprehensive distribution maps. Models are required because the ocean is vast and surveys are very expensive, so the bird counts are incomplete in space and time. Models allow us to essentially fill in those information gaps using estimated relationships between the occurrence of birds and environmental conditions.

Our final maps indicate where and when each species of marine bird is relatively more or less abundant throughout large regions of U.S. waters. To date we have produced maps for more than 80 species across the east coast, the contiguous west coast, and the Main Hawaiian Islands. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management uses these maps in their offshore wind energy planning process to assess where and when the potential for impacts on marine birds is greatest, thereby allowing them to anticipate and minimize those impacts.

Kevin: NCCOS’ Ecosystem Science priority is broad due to the complex nature and geographic extent of coastal ecosystems, not to mention the many natural resource conservation issues they present. As a result, NCCOS has developed four sub-priority focal areas of importance to managers. These are

Marine Spatial Planning (hereafter referred to as MSP), Habitat Mapping, Biogeographic/Ecological Assessments and Research, and Research and Monitoring in Coral Reef Ecosystems.

Next we’ll hear from NCCOS Chief Scientist Dr. Mark Monaco explaining the history of marine spatial planning within NCCOS, one of our most valued areas of expertise.

Mark Monaco: NCCOS Marine Spatial Ecology Research and Assessment portfolio includes Marine Spatial Planning, or MSP, as a key approach to support coastal, ocean, and Great Lakes spatial ecosystem management. MSP is a data-driven approach to managing space to balance environmental, economic, and social objectives, minimize conflicts and optimize sustainable use of marine resources. NCCOS and its predecessors have been conducting geospatial research and developing tools for over 50 years to support marine resource management through conservation and restoration activities. Our MSP portfolio includes inventory and mapping human uses of the coastal ocean to aid in minimizing spatial conflicts among users when siting ocean industries and conservation areas, such as marine protected areas (or MPAs).

NCCOS has a long history in developing geospatial assessments and associated products to support NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary Program, finding boundaries for new sanctuaries, assessing ecological relevancy of existing boundaries for adaptive management. This includes the modification of the configuration of existing boundaries and boundary expansions. This is often done using NCCOS’ biogeographic assessment framework, as it provides a flexible and multi-disciplinary approach to integrate geospatial information into formats and visualization tools readily usable for spatial planning. The biogeographic assessment framework includes characterization and mapping of the distribution of habitats and associated living resources within and around NOAA’s marine sanctuaries to support development of sanctuary condition reports that provide key information to update sanctuary management plans.

The robust NCCOS MSP and biogeographic assessment portfolio provides key products to remote and advanced ecosystem based management (or EBM). EBM is an integrated approach that in corporates the entire ecosystem, including humans, into resource management decisions and is guided by an adaptive management approach. NCCOS’s geospatial research and approaches directly support the National Ocean Service’s strategic plan goals, including the goal to conserve, restore, and connect healthy coastal, ocean, and Great Lakes ecosystems.

Kevin: The NCCOS Competitive Research Program (CRP) funds regional-scale research through a competitive, peer-reviewed process to

address our nation’s most pressing ocean and coastal issues. CRP is the extramural branch of NCCOS, directly supporting the research needs of the National Ocean Service offices and resource managers. CRP expands NCCOS capabilities to meet stakeholder needs by funding external research. Here’s Marc Suddleson to explain a little more about the program.

Marc Suddleson: For 35 years the Competitive Research Program has provided research, monitoring, assessments, and technical assistance for NOAA. Our office has been with NCCOS from the start. Throughout our history, we have supported the development of actionable scientific information and new tools to improve the protection, management, and conservation of ocean, coastal, and Great Lake ecosystems. CRP regional scale and targeted research projects address the most pressing coastal and Great Lake challenges facing our nation. These include harmful algal blooms, low dissolved oxygen (or hypoxia), coastal resiliency, sea level rise, ocean acidification, and the effective management of critical and unique ecosystems.

As the extramural arm of NCCOS, CRP directly supports the research needs of the National Ocean Service. The CRP team engages resource managers, policy makers, impacted communities, and the scientific community through a variety of means to identify our research priorities. We also build engagement into our projects through technical advisory committees, for example, to ensure our research products and outcomes support sound, scientific based decisions.

CRP is a national leader in harmful algal bloom and hypoxia research and implements competitive programs authorized by congress through the Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research Control Act. CRP harmful algal bloom and hypoxia programs are advancing research on ecosystem impacts, detection, monitoring and control methods, and providing new and improved forecasting and observing capabilities to help NOAA and our government and industry partners keep pace with expanding HAB problems and to mitigate their often devastating environmental and economic impacts.

CRP also provides science to help coastal communities and safeguard coastal economies facing climate and ecosystem changes and increased extreme events. Our sea level rise program conducts scientific assessments and provides information and tools, such as storm surge modeling that coastal communities can use to make sound ecosystem-based, risk management decisions.

CRP ocean and coastal acidification research advances understanding and predictions of impacts as carbon dioxide levels rise in our coastal waters. CRP regional scale research on ecosystem connectivity and multiple stressors develops data, tools, and predictive models that enable ecosystem managers to evaluate and improve spatial management strategies. Our research has brought awareness and broadened the understanding of low-light coral ecosystems, which make up about 80 percent of the worlds’ coral reefs.

Kevin: Yet another focus and expertise found in NCCOS is science on the adaptation to sea level rise, coastal inundation, and climate impacts. In addition our work also informs the mitigation of both chemical and biological stressors.

This is Kimani Kimbrough discussing NCCOS’ National Status and Trends program. Begun in 1984, this program is the longest continuous monitoring program in the country. Having routinely sampled coastal sites for a wide variety of contaminants, the data from the program can, for example, be used to demonstrate the impact of a disaster, either natural or manmade, on contaminant distribution and levels in the affected area.

Kimani Kimbrough: The NCCOS National Status and Trends Program (or NS&T) has a large dataset that includes over 30 years of sediment and tissue contaminant data from throughout the U.S. and territories. NS&T has participated in the response to oil spills, hurricanes, the attack on the World Trade Center, and other disasters. The ongoing programs include the National Mussel Watch long term monitoring program that samples mussels and oysters annually, with some of the sites having been sampled for decades. Another program of NS&T is the bioeffects assessment program that has performed assessments throughout the U.S., including the Great Lakes, Caribbean, Hawaii, and Alaska. Studies include remediation effectiveness, baseline determination, and stakeholder requests. NS&T has results for over 500 compounds from a variety of organisms, including oysters, blue mussels, freshwater mussels from the Great Lakes, and fishes. Hundreds of reports have been published to support local and resource management and policy. Combining relevant data from all NS&T programs represents a unique opportunity to find additional information from studies with different sampling designs and temporal scales. Utilizing artificial intelligence, we have characterized contaminants nationally and unlocked relevant information that supports more efficient monitoring, management decisions and contaminant prediction. In a fast moving world, we use the combination of AI and historic data to more accurately assess contaminant risk.

Kevin: Developing and implementing advanced observation technologies and ecological forecasts is another key component of NCCOS science. From annual predictions of the Gulf of Mexico dead zone, to forecasting harmful algal blooms in the Great lakes and Gulf of Maine, NCCOS research helps regional resource managers prepare and adapt to changing and often harmful, environmental conditions. Let’s hear from Dr.Terry McTigue, about a new harmful algal bloom forecast that is being developed for the Gulf of Alaska.

Terry McTigue: While harmful algal blooms occur in many parts of the U.S., they’re particularly a problem in Alaska. Shellfish have been harvested for generations by indigenous people, particularly in the Kodiak archipelago. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to monitor the shellfish beds because of the great distances involved and travel issues. People have died there after consuming shellfish tainted with harmful algal bloom toxins. NCCOS has been successful in developing forecasts elsewhere in the U.S. for when and where red tides and other harmful algal bloom events are likely to occur.

In partnership with the Kodiak Area Native Association and Alaska Sea Grant, we’ve started the development of a red tide forecast for the Kodiak archipelago. A functional forecast for the area would give people several days warning that a red tide event is likely to occur and in what location. Community members would be able to avoid harvesting clams during those periods, helping to protect their health. It’s going to be a multi-year process, but with great partners and such a pressing need, we’re committed to creating a forecast and supporting the Kodiak communities.

Kevin: The complex challenges of sea level rise, coastal flooding, harmful algal blooms, and water pollution, among other hazards, pose increasing risks to coastal communities. In the five-year period spanning 2016– 2020, weather and climate-related natural disasters cost the U.S. over $616 billion. Losses of this magnitude are projected to become commonplace due to a changing and increasingly turbulent climate that is changing our coastal ecosystems, and the coastal communities and economies that rely on them. Further, the concentration of human activities on our coasts leads to additional pressure and inevitable competition over the use of our natural resources for commerce, food, energy, recreation, and conservation. With 40 percent of the U.S. population living in coastal counties and with that number only expected to increase, it is clear that a significant portion of the nation’s population, including some of our most disadvantaged communities, are becoming increasingly vulnerable.

This is Brandon Puckett from the Beaufort Lab explaining some of the work done there that informs our understanding of coastal resilience.

Brandon Puckett: Broadly speaking, resilience is the ability to absorb, recover, and adapt to stressors. And when we think about coastal resilience we’re applying that definition to coastal communities as well as coastal ecosystems such as salt marsh, wetlands, oyster reefs, and coral reefs. Stressors along our coast include episodic extreme events like hurricanes along with more gradual processes like sea level rise. And we should not forget that our coastal development is also often a stressor on the coastal ecosystems on which we depend. We ask how ecosystems can help protect coastal communities from coastal hazards. We measure and model reductions in wave energy, shoreline erosion, and inundation provided by coastal ecosystems. For instance, 100 feet of marsh can reduce 90 percent of the incoming wave energy in much of our estuarine environments. And coral reefs function the much the same in reducing wave energy in nearshore coastal environments. In turn, this helps protect coastal communities. Importantly, we are working on determining the limits of these protected services again using field measurements and modeling, we’re asking questions like “how big would a storm have to be?” or “how high would sea levels have to rise such that coastal ecosystems can no longer provide as much protection?” Lastly, with a better understanding of how coastal ecosystems respond and adapt to stressors and what protective services those systems provide now and into the future we can better assist with, not only the management of coastal ecosystems, but also assist with siting and designing projects to harness nature to enhance resilience of our coastal communities.

Kevin: The far flung Kasitsna Bay laboratory in Alaska is a small but vibrant outpost of NCCOS research. The lab partners with the University of Alaska Fairbanks on lab operations and research. The Kasitsna lab focuses on coastal impacts of climate change, ocean acidification, harmful algal blooms and oil spills, and hosts federal, state, tribal, and university researchers.

This is Reid Brewer, the lab’s current director, explaining the need for such a lab.

Reid Brewer: The Kasitsna Bay Lab in Homer, Alaska is excited to be celebrating the NCCOS 25th anniversary. Though this marks the 25th year NCCOS has managed the Kasitsna Bay Lab, the lab is also celebrating its 65th anniversary since its inception. Similar to other NCCOS labs, the Kasitsna Bay Lab supports coastal research and science that serves coastal communities. Different from other NCCOS labs, Kasitsna Bay Lab is located on the west coast of the United States, has a kelp dominated nearshore ecosystem, and boasts much colder water temperatures.

Regardless of location, NCCOS staff and researchers work collaboratively to meet the NCCOS goals of bringing to bear a suite of specialists that work to answer questions and create tools that serve our coastal communities. To celebrate this, our 25th anniversary, the Kasitsna Bay Lab is hosting two days of events with Kachemak Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve–also celebrating 25 years–to bring together researchers, administrators, tribal organizations and community members. Attendees will be doing a watershed tour and storytelling event with the KBNERR and a community barbeque event and open house with Kasitsna Bay Lab. Over the two-day event, attendees will be sharing stories, meeting with colleagues, and learning about the roles of NCCOS and the KBNERR. We are all excited to be a part of this special event.

Kevin: The Cooperative Oxford Laboratory is a partnership between NOAA, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and the USCG Station Oxford. The Oxford lab partners combine science, response, and management capabilities to meet their respective missions and regularly collaborate to address science and management challenges. The scientific capabilities of The Oxford lab researchers along with those from the Maryland DNR are diverse, and include expertise in field ecology, advanced underwater acoustic technologies, fish health, sea turtle stranding response, and many others.

Here is Jason Spires from the Oxford Lab describing recent efforts to restore oyster restoration efforts in the Chesapeake Bay.

Jason Spires: In coastal ecosystems, wild and formed oysters function as keystone species providing vital habitat for fish and vertebrates and play an important role in water quality. Intact oyster reefs are shown to remove nutrients from estuaries, improving water quality. In addition to ecosystem services, the eastern oyster supports coastal economies from Maine to Texas. Ongoing efforts to restore eastern oyster populations in many regions rely on the stockings of juveniles spat on shell to rebuild populates. Often remote setting is used, which entails releasing hatchery produced larvae into tanks filled with oyster shells. Although this production method has proven effective and is the primary means of spat on shell production across the eastern oyster industry, it requires the acquisition, cleaning, transport, storing, and loading of large quantities of shell. In Chesapeake Bay and other regions, shell is costly and availability is decreasing. Hence cost saving alternatives to traditional methods are being investigated.

At NCCOS’ Cooperative Oxford Laboratory, we are working on a technique that reduces the reliance on reclaimed oyster shell by putting oyster larvae directly into their natural environment on intact oyster reefs in the water, skipping the acquisition of shell. This technique is called direct setting. Currently NCCOS is partnering directly with industry, researchers, and resource managers in the states of Maryland, Texas, and Mississippi to test direct setting methods in various estuaries. If successful, this method has the potential to support coastal economies by providing a cost-saving alternative to traditional oyster planting methods to farmers, harvesters, and resource managers.

Kevin: In addition to the activities that Jason just described, the lab researchers also contribute to efforts that not only influence the health, but the economy of the Chesapeake Bay.

NCCOS research has played a major role in many national stories concerning the coastal environment. Here is Dr. Peter Etnoyer, lead scientist for the Deep Coral Ecology Lab at the Hollings Marine Lab in Charleston discussing some of the work associated with the Deep Water Horizon Oil Spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Peter Etnoyer: We started out exploring a lot of America’s uncharted deepsea terrain. We used submersibles, robots, AUVs, ROVs, all kinds of technologies to map the seafloor and explore it. Over the years we’ve been around the country, from Alaska, California, southeast U.S. and more and more working in the Gulf of Mexico. Wherever we’ve observed the seafloor and noticed hard bottom outcrops, whether they be banks or mounds or ridges, seamounts on the seafloor, or wherever there’s kind of abrupt topographies occur, we find deep sea corals, sponges, fish, shrimp, crabs. These rich, abundant habitats and deep, cold water where people haven’t traditionally expected them to be. We use this information to provide to fishery management councils that make decisions on how to use our offshore resources, uh, the fish that occur there, wind energy, the oil and gas. All these different interests are at play. And deep down at the bottom of the ocean are these corals that are hundreds of thousands of years old. And there’s these communities that have grown up around them. There’s these sensitive habitats and need to be protected. What we’re doing differently that we didn’t used to do is we’re bringing these corals back alive and keeping them in aquaria, figuring out how they reproduce, what they eat. And we’re doing that because we have a need to grow these things and replace them in the Gulf of Mexico below the oil slick caused by the Deepwater Horizon incident. This has been the focus of our work since 2014 or so. And we’re slowly figuring it out and keeping them alive from as deep as 1000 meters for as long as three years so far. So it’s going well. We’re learning more every day.

Kevin: Investing in our People and Achieving Organizational Excellence is a core value at NCCOS. Here is the current Deputy Director Margo Shulze-Haugen explaining why this is so important to NCCOS now and in the future.

Margo Shulze-Haugen: The dynamic nature of ecosystem science and the needs of our coastal communities make it very important to stay flexible in the approach to our work. We believe that by enabling our scientists to use their expertise in their research, while supporting their staffing, financial, and facilities needs is the best way to do that. Knowing that they have reliable access to available resources, our scientists are able to conduct top-notch field and lab research, lead cutting edge modeling and technology advancements and innovate freely while taking on new challenges. Further, our work with the Sea Grant Knauss Fellowship means we are constantly bringing in new, up and coming marine researchers to keep our perspective fresh and evolving.

Kevin: NCCOS has now been in existence for a quarter of a century and the wide-ranging work being done here is more relevant than ever. With continued support from a broad and dedicated user base of our science and products, the story of NCCOS will continue to expand and enhance our knowledge of the coastal environment and our interactions with it, well beyond this 25-year anniversary.

You have been listening to Coastal Conversations, an occasional podcast from the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, thank you for listening.