Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of fabricated chemicals that have been used in a variety of industries since the 1940s, including food packaging, commercial household products, and electronics manufacturing. PFAS compounds have been documented in marine and estuarine waters worldwide and levels have been found in estuarine fish and invertebrates. Our research with PFAS adds much needed data to assess how these contaminants pose a risk to the health of estuarine organisms.

Why We Care

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are found throughout the environment. Currently, little is understood about the potential ecological risk posed by these substances, particularly in marine environments. The objective of these studies is to assess the toxicity and bioaccumulation (the ability for a substance to build up in an organism over time) of PFAS compounds in model marine and estuarine organisms to support ecological risk assessments and remediation decision-making.

What We Are Doing

Out of the thousands of PFAS compounds that exist, we are focusing on select PFAS that have been prioritized by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and are of the most commonly found in the environment — PFOS, PFOA, PFBA, PFHxS, PFHxA (identified in this EPA Fact Sheet). We started with basic toxicity studies with juvenile and larval life stages of estuarine animals, including grass shrimp, sheepshead minnows, mud snails, mysids, and red drum. Previous studies with these organisms have shown that juvenile and larval stages are the most sensitive to contaminants.

In our PFAS studies, the fish and invertebrates were exposed to several concentrations of the PFAS compounds for 96 hours (acute exposures) to determine a concentration that is lethal to 50 percent of the animals that were exposed. After determining these levels, we dug deeper into how toxicity could change under different scenarios.

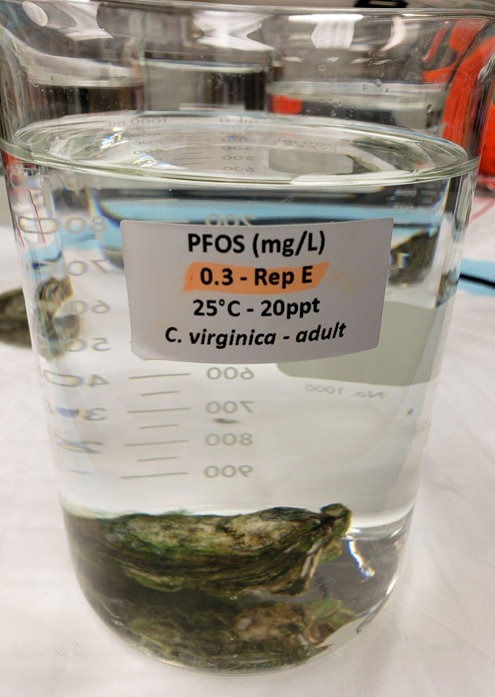

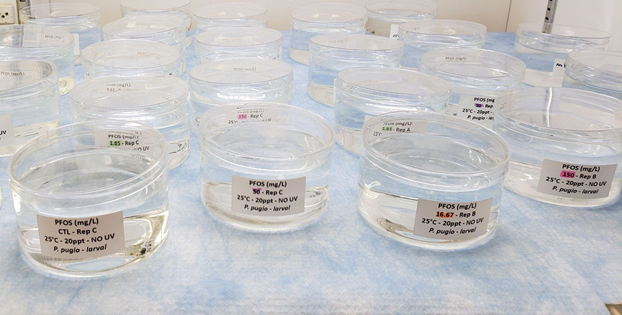

To see if organisms under stress due to various environmental factors will affect toxicity, we altered the temperature and salinity during PFOS exposures in fish and invertebrates. We tested sheepshead minnows to see if mixtures of different PFAS compounds will affect toxicity. We also researched the uptake and depuration of PFOS in oysters. In other research, we exposed grass shrimp larvae to four different PFAS compounds to determine any effects on larval development. While our laboratory studies have helped establish toxicity thresholds for larval fish and invertebrates for PFAS, we also investigated the chemical fate and biological effects of PFAS in a mesocosm (simulated tidal creek system).

What We Found

Multistressor interactions with PFOS and four estuarine organisms showed that salinity and temperature can have an effect on PFOS toxicity. The effects of increased temperature (32°C) and decreased salinity (10 ppt) varied with test species. PFOS toxicity for the sheepshead minnows increased with temperature, but was not altered by decreased salinity. For grass shrimp and mud snails, PFOS toxicity was greater under lower salinity. The combination of higher temperature and lower salinity was observed to lower the toxicity thresholds for all species.

In the mixture studies with embryonic and larval sheepshead minnows, PFOS alone was acutely toxic to larvae. A PFOS and PFOA mixture resulted in lower larval toxicity suggesting an antagonistic effect. These observations were supported by biomarkers of exposure that indicated reduced oxidative stress in the mixtures compared to PFOS alone. While PFOA reduced PFOS-induced mortality PFHxA and PFBA did not. Additional research will investigate the relationship between chemical structure and molecular mechanisms in determining PFAS mixture toxicity.

Biomarker analysis in oyster tissue along with chemical analysis of PFOS in oyster tissue and water samples revealed the oysters’ ability to overcome exposures without significant damage to lipid membranes. However, significant cellular lysosomal damage was observed. The oysters were able to eliminate up to 96% of PFOS exposures when allowed to depurate for two days in clean seawater. Results provide insight into possible detrimental cellular effects of PFOS exposure in addition to offering insight into contaminant persistence in oyster tissue.

Chronic exposures of grass shrimp larvae to four PFAS compounds indicated the potential for developmental delays. While this study showed physical changes are possible in grass shrimp larval development; we still do not know what cellular and sub-cellular effects are occurring, which may happen at lower levels of exposure.

Our work with mesocosm research found that shrimp were the most sensitive to PFOS, while invertebrate amphipods were the most sensitive to PFOA with no effect on fish or adult snail survival. Chemistry results showed a rapid partitioning of the PFAS compounds from water to sediment and PFOS accumulated more readily than PFOA in exposed organisms.

Benefits of Our Work

The data generated from our research demonstrates that expanding toxicity testing to include a wider range of parameters will improve the environmental risk assessment of PFAS contaminants, especially for species inhabiting dynamic estuarine ecosystems. Determining the mechanisms of toxicity and interactions between PFAS will aid environmental regulation and management of these ubiquitous pollutants. Regulation of PFAS compounds is rapidly moving forward within the EPA, which has proposed a Freshwater and Saltwater Benchmark for PFOS and PFOA and other PFAS compounds.

Next Steps

We are continuing our work with PFAS compounds by looking into chronic exposures with the most sensitive species, researching the mechanism of PFAS toxicity in estuarine organisms, and determining the effects of PFAS mixtures on these aquatic animals.