The Loop Current in the Gulf of Mexico, a dominant oceanographic feature, often intrudes far into the Gulf, shedding clockwise circulating eddies. NCCOS-funded marine scientists with the University of South Florida are working to explain the cause of Loop Current intrusion and eddy formation, which are not well-understood, as the behavior of the Loop Current is of regional ecological importance.

The Loop Current is an area of warm water that travels up from the Caribbean between the Yucatan Peninsula and Cuba (as the Yucatan Current) and into the Gulf of Mexico. As the current exits the Gulf through the Straits of Florida (as the Florida Current) it meets the Antilles Current to form the Gulf Stream. The Loop Current may either intrude far into the Gulf of Mexico or take a more direct path to the Atlantic Ocean. Oceanographers have conducted numerous theoretical investigations of the control mechanism for intrusion and eddy formation versus direct exit to the Gulf Stream.

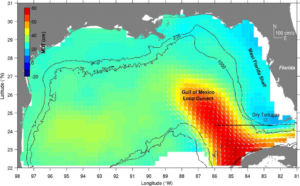

Results from the study describes Loop Current variability using more than 24 years of satellite altimetry‐derived sea surface height data. The study employed a neural network modeling technique called “Self-Organizing Map” or SOM to produce visual “snapshots” of sea surface height anomalies to picture the Loop Current.

This shows the importance of the West Florida Shelf (WFS) in controlling Loop Current behavior. When the Loop Current meets the shallow waters of the southwest corner of the WFS near the Dry Tortugas (termed a “pressure point”), it becomes “anchored” and flows more directly through the Florida Straits. Loop Current anchoring stimulates upwelling of nutrient-laden deeper water into the WFS and facilitates ecologically significant activities such as transport to nearshore of gag grouper larvae, Karenia brevis red tide, and the movement of Deepwater Horizon oil (all research NCCOS funded).

The study reveals that when the Loop Current strays from the WFS it becomes “unanchored” and released, penetrating northward into the Gulf and shedding anticyclonic (clockwise) flowing eddies. These intrusions and eddies can travel as far north as the Mississippi River Delta and as far west as Texas.

The study is supported by the NCCOS Prevention, Control, and Mitigation of Harmful Algal Blooms Program (PCMHAB). Some earlier project findings are reported here.

Citation: Weisberg, R. H. and Y. Liu. 2017. On the Loop Current penetration into the Gulf of Mexico. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 122: 9679–9694. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JC013330

For more information, contact Quay.Dortch@noaa.gov.