Contaminants of Emerging Concern

NCCOS conducts research to evaluate and predict the effects of chemical contaminants and other environmental stressors on coastal ecosystems. Estuarine environments can serve as sinks for many chemical contaminants bound to particulate matter as they move through urban and agricultural watersheds into rivers and are deposited in coastal areas where sedimentation rates are high. Headwater streams, such as tidal creeks in the coastal zone, are most susceptible to chemical runoff. These areas also serve as critical habitats supporting nursery grounds for estuarine fish and invertebrate species. These systems are vulnerable to many anthropogenic stressors, including land development, agriculture, urban and resort runoff, and point and nonpoint source inputs.

Contaminants of emerging concern describe a wide range of chemicals that are broadly defined as any synthetic or naturally occurring chemical that is not commonly monitored in the environment but has the potential to enter the environment and cause known or suspected adverse ecological and/or human health effects. In some cases, release of emerging contaminants to the environment has likely occurred for a long time, but may not have been recognized until new detection methods were developed. In other cases, synthesis of new chemicals or changes in use and disposal of existing chemicals can create new sources of emerging contaminants. Examples of contaminants of emerging concern include:

Ecotoxicology

NCCOS works to determine toxicity thresholds associated with environmental pollution by developing sublethal indicators of contaminant exposure and stress and by evaluating impacts of priority contaminants, contaminant mixtures, and multiple stressors. Our scientists also improve risk assessments for environmental and human health while supporting national and regional chemical contaminant assessments.

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are man-made chemicals used in industrial and consumer products to increase resistance to heat, stains, water, and grease. PFAS can persist in your body and in the environment for decades causing harmful effects for populations of humans and marine life. NCCOS is measuring PFAS in coastal ecosystems and studying the biological and ecological effects. This research will identify risks for coastal, marine, and Great Lakes environments and in living marine resources. Federal and state agencies translate our data into solutions and management actions that mitigate pollution impacts and protect environmental health, living marine resources, and seafood safety.

Pharmaceuticals in the Environment: Antimicrobial Pollution and Resistance

Over 200,000 metric tonnes of antibiotics are used annually for human and veterinary medicine, livestock production, and aquaculture. Antimicrobial compounds in municipal wastewater, stormwater, and agricultural and aquacultural inputs can establish chronic low-level exposures in marine and estuarine ecosystems. This may lead to the presence of antibiotic resistance, where bacteria in the water develop resistance to the compound’s mechanism of action and become the dominant form. Antibiotic resistance can then spread to the gut flora of marine organisms, and to human consumers, which may reduce the effectiveness of antimicrobial treatments when they are needed. Antimicrobial compounds in the environment may also promote the growth of pathogenic microbes, reducing the safety of recreational and commercial coastal activities.

Microplastics in the Coastal Zone

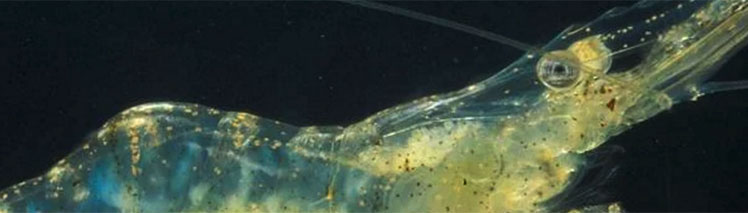

Microplastics are ubiquitous in the world’s oceans, lakes, and rivers. These small plastic particles and fibers have been a focus of recent research studies on marine animals because of their potential to cause physical harm, and to transport pathogens and harmful chemicals into the organism. NCCOS is studying the distribution of microplastics in coastal ecosystems and is examining impacts of microplastic ingestion in coastal species.

Marine Mammals

Since 2017, the Coastal Marine Mammal Assessments Program has been refining the methodology for extraction of microplastics from the gastrointestinal tracts of dolphins, quantifying those microplastics, and then identifying the associated microplastic polymers. NCCOS is monitoring temporal and spatial trends in microplastic densities and polymer types of plastics ingested by bottlenose dolphins stranded in South Carolina. Our research helps to determine the effects of microplastics and associated contaminants on the health of marine mammals.

Coastal Marine Mammal Assessments

Oysters

NCCOS is studying how microplastics affect oyster health. Oysters were exposed to microplastics in the laboratory to examine uptake and physiological impacts. These studies have included combining environmental stressors such as pathogenic bacteria (Vibrio) and harmful algae (Microcystis) with the microplastics to see the interactive effects on oysters. NCCOS scientists are also sampling oyster beds to quantify the number and types of microplastics in the oysters, the sediment, and the water.