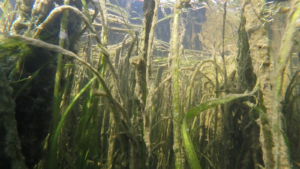

A new publication by a team of researchers supported by NCCOS and the NOAA Ocean Acidification Program has found that dense seagrass beds in the upper Chesapeake Bay generate “buffering capacity” against acidification in the lower Bay. In summer, high rates of photosynthesis by seagrasses at the head of the Bay in an area known as the Susquehanna Flats (and in other shallow areas) create chemical conditions that favor the formation of calcium carbonate particles over the beds. These are subsequently transported downstream into more acidic Bay waters, where they dissolve and buffer the system, decreasing acidification.

Uptake of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere has made the Bay and the world’s oceans more acidic and has threatened the health of marine organisms and their ecosystems. In coastal waters, carbon dioxide is also produced by biological respiration, which can contribute to coastal acidification.

The findings suggest an additional, unanticipated benefit of nutrient management efforts in the Bay. Reducing nutrient inputs into coastal waters will be good for seagrasses themselves, and will improve water clarity, decrease hypoxia (low oxygen levels in the water), and help to alleviate the severity of coastal ocean acidification.

Read more about the study in the University of Delaware’s UDAILY.

For more information, contact Beth Turner or Erica Ombres or see the original publication here.