As recent as 2012, Texas was impacted by the longest red tide on record, leading to the collapse of its oyster industry and the Governor to seek disaster assistance from the U.S. Department of Commerce.

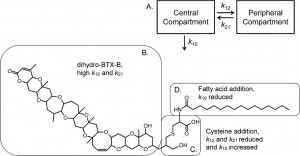

A new study shows that in animals the brevetoxin cysteine conjugate eliminates quickly from the blood, whereas the highly toxic brevetoxin lipid conjugate eliminates slowly. The study reveals the types of changes to the toxin molecule that increase or decrease toxicity and provides the first toxicokinetic parameters for the red tide toxin that describes and models the rate it enters the body, how long it stays, and how long it takes to be eliminated: factors that change the outcome of neurotoxic shellfish poisoning.

Red tides in the Gulf of Mexico affect humans, wildlife, fisheries and the regional tourist-related economy. They are caused by the harmful algae Karenia brevis, which release a powerful a neurotoxin called brevetoxin. Research shows that brevetoxin is highly reactive and attaches to proteins and lipids, leading to hybrid “conjugate” molecules that are hard to detect and threaten human and animal health.

Collaborating with researchers in New Zealand, NCCOS scientists used chemical synthesis to prepare brevetoxin conjugates that pose the greatest risk to Gulf of Mexico shellfish consumers, to test how they may affect humans and animals. Initial studies showed that the common shellfish brevetoxin which is attached to the amino acid cysteine had little effect on its toxicity or on the ability of test methods to safely reopen shellfish harvests. By contrast another shellfish metabolite, brevetoxin attached to a lipid, greatly increases its toxic potency and escapes existing test methods.

Expanding the knowledge of the toxic properties of brevetoxins will help refine strategies to reduce its risk to humans, improve resiliency of local fishing industries and mitigate economic impacts.